Every age creates its signature way of telling and consuming stories. The Jacobeans had the blood and lust of popular tragedy. The Victorians had the great social novel. The 1960s had new journalism. The chosen form of our own age is the downloaded serial drama. While the energy and ambition of screenwriters was for nearly a century invested in two-hour feature films, for the past 10 years, ever since The Wire and The Sopranos and The West Wing showed what might be possible, it has been in the 10-hour arcs, and annual seasons of streamed drama.

Those shows – Scandi-noir, Game of Thrones (and its progeny), Breaking Bad and the rest – have created a new kind of relation between creators and viewers. The stories are made not only for total immersion, but also presuppose the potential for binge-watching. Since Netflix started uploading whole series, days and nights are lost to the “just one more episode” of unfolding dramas, in the way that we might once have been invited to lose ourselves in books.

The idea of bingeing on drama has some negative connotations, but the facts suggest that far from seeing this habit as time wasted, we tend to think of it as fulfilling in the way that time devoted to great fiction always was. In 2013, Netflix did a study into why 73% of viewers felt overwhelming feelings of comfort when immersed in these dramas. The company sent an anthropologist, Grant McCracken, into viewers’ homes to discover the reasons for this: “TV viewers are no longer zoning out as a way to forget about their day, they are tuning in, on their own schedule, to a different world. Getting immersed in multiple episodes or even multiple seasons of a show over a few weeks is a new kind of escapism that is especially welcome.” The usual attention deficit of the internet was replaced by something more complex and satisfying.

The huge demand for such shows and the intense rivalry between Netflix and Amazon, in particular, to create has led to a new kind of mythologised creative space: the writers’ room. The creative pressures of producing multiple series of 10-hour dramas in short order have changed the dynamic of traditional scriptwriting practice. Rather than pairs of writers, or single auteurs, the collective and the collaborative is not only prized but essential.

As favourite shows build their own addictive fanbases – more fragmented than the audience for broadcast TV ever was, but often more cultishly engaged – the writers’ room, the place where the drama begins and ends, has become the subject of intense curiosity and scrutiny. The room is largely an American creation, a development of the comedy bunkhouses that produce The Simpsons or Saturday Night Live. Inevitably there are websites and blogs and memes devoted to gossip about these sacred and profane spaces, places to get a fix of favourite dramas before the next series is uploaded. Some shows – Orange Is the New Black and The Good Wife pioneered the practice – provide the backstory to the genesis and creation scenes in live Twitter feeds, with whiteboards and interview links and photos.

What they mostly reveal is that having ideas – even in groups – and writing them up into scripts is no less painful and laborious than it ever was, but that it now has a kind of endless forward motion.

In his book Difficult Men, Brett Martin describes the rise of the21st-century phenomenon of the streamed drama series, noting that though all writers’ rooms have their own character, they share a few common features. Chief among them, the one “near-absolute” is that in the centre of the room “there will be a quantity and flow of food reminiscent of a cruise ship, as though writing were an athletic feat demanding a constant infusion of calories”.

Other than that energy supply, there are two essential elements: along one wall a whiteboard (“the signature tool of this golden age”) with a grid divided into 10 or 12 columns, one for each episode; and a harassed-looking writers’ assistant feverishly trying to capture every passing comment made by the writers in relation to those episodes and to type it into a laptop before it is lost.

At the centre of all of the chat and ideas is the showrunner, the person charged with getting the writers writing and the series made. This person is rarely relaxed. As David Chase, creator of The Sopranos observed: “Other people have good ideas. And they’re hard to come by. But in another sense, they’re a dime-a-dozen. Turning an idea into an episode – that’s the grunt work. Eventually, the showrunner’s the one who has to look at his watch and say: ‘How do we fill up 42 minutes?’ We can all sit around and decide we want to make a Louis XIV table, but eventually somebody has to do the carving.”

Different writers’ rooms have evolved different processes to try to keep that grunt work going into the fourth and fifth and sixth series. Here, three showrunners explain how they do it.

‘Eric Newman, Narcos: People come and go, but you burn out pretty quickly’

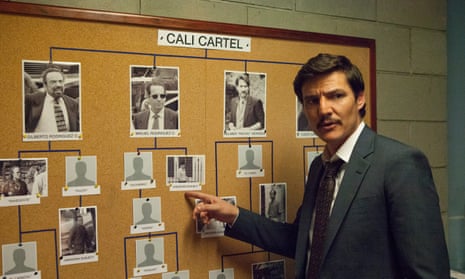

Eric Newman, producer of genre films such as Dawn of the Dead and Children of Men, spent years researching the rise and fall of Pablo Escobar and the Colombian cocaine trade, with a view to making a feature film of the story. Netflix approached him with the idea of a series, and he offered them the first 10 hours of Escobar’s story. The third series of Narcos, which shows the rise of the Cali Cartel after Escobar’s death, began on Netflix this month.

“This is something I have been living with for 20 years. From the beginning, I wanted this not to be about one trafficker, Escobar. I wanted it to be about a whole evolution of this business.

We have been talking about this series, the macro of it, for what seems like forever. In terms of the process we have what we call tent poles of events, things that happen, turning points that support the rest of the story. Some of them are spectacular, others more subtle – from the end of the cold war to the death of a cop. As writers, we have these events to hit. We take licence occasionally, but there is an obligation to the truth.

The writers’ room is where the research comes together. The nature of the job means above all we all have to know the story inside out. All the characters, where they wanted to go, and how close they got, and where they ended up. All drama arises in the gap between what a person wants and what they get. We always try to talk about the characters as the real people they were: ‘Where is this guy going? What does he want?’ All we will do for the first six to eight weeks in the writing room is just talk about the story. Nothing makes me happier than when one of the writers comes in and says: ‘Look, I found out this amazing thing about this guy last night – how can we use it?’

We are always learning new stuff as we go. One of my favourite things in series two was this guy named Limón. All we had was that there was this guy and he was shot and killed with Escobar. We thought: well, if that is where his story ends, where does it begin? And we came up with this really compelling story in the second episode of season two. We do that a lot. We have a car crash and then trace it backwards.

It is a very difficult and complicated and exhausting process. In any writers’ room – and this is the first show I have written and run – there are two invaluable things: one is inspiration, and the other is those collaborators who have done research. We talk to everybody who was involved, though not to the traffickers that much because they give the same story: they were misunderstood, innocent, not as they were depicted.

Our guiding thematic principle is that this world is extremely complicated. It is never bad guys and good guys. It is bad guys and very bad guys. And there is almost never any justice, only a doomed mission that is underneath it all. By episode seven, we know Escobar will have blown up an airplane. But how he gets there is the fun part. He is a character like Icarus, or Macbeth. An archetype and also the truth. Our job is to find the most dramatic version of that. The veracity of it gets more imperative. I think we are somewhere around 60% to 70% true. But what you find is that this world is full of unreliable narrators, wishful thinkers, self‑deceivers.

I come from movies, and we look at things in terms of a three-act structure. What everyone wants and why they can’t get it has to be established very clearly in the first act. The middle act tends to be an escalation of things, leading in the third act to a massive confrontation. Doing that over 10 hours kind of explodes the drama. Some of the younger writers in the room have grown up with this TV format. Right now we have 10 writers, and the younger ones have had experience primarily in television. For a screenwriter, that always used to be seen as a failure. Now it is the opposite. It has changed over the last 10 years, but particularly since The Wire and The Sopranos, that first golden age of cable television.

I would say in terms of all three seasons I may be the only consistent presence in the writers’ room. People come and go, but you burn out pretty quickly. Every morning I wake up and I attempt to convince my wife that I have no idea what I am doing and that this is the season that will expose me. And then I drive to the office, and almost invariably, after about an hour staring at this massive whiteboard with all the characters and diagrams of who killed whom, we find inspiration. It is like being in a police operations room. The key thing is that this is not a job, and if you try to approach it like a regular job you can’t do it. It requires a level of commitment that only comes if you love it and are interested enough in it to talk about it until exhaustion.”

Jill Soloway, Transparent: ‘We want the characters to tell us what they want’

Jill Soloway is the creator of Amazon’s Transparent, the comedy drama that returned for a fourth season on Amazon last week. Soloway previously worked as a writer on several other series including Six Feet Under and was best director at the Sundance film festival in 2013 for the feature Afternoon Delight.

Transparent stars Jeffrey Tambor as Maura Pfefferman, a retired college professor who opens up to his family about having always identified as a woman. Soloway’s father came out in a similar way in 2011. Tambor and Soloway, who now identifies as nonbinary, both won Golden Globes for Transparent in 2015, the first time an internet-streaming show had won the award for best series.

“I think of our writers’ room like the perfect dinner party or the perfect gathering. You want a whole bunch of different opinions in there and yet you don’t want to get bogged down in conflict. I look for people who understand how to play well with others but who are also strong personalities. In terms of writers, you want people who are shit-starters creatively, but not in real life.

We have been quite a tight team, but for season five of Transparent, which we are writing now, we are having a little transition – losing a few writers and gaining some. We are having more trans women in the writers’ room; we actually have three trans women and five trans people in total if you count people who are gender-nonconforming. It’s exciting to slowly make the room reflect the possibility of the story.

It is always like a group commitment, Monday to Friday. Sitting in that room on the beanbags and dreaming up the characters is the most fun thing ever. I will spend slightly less time there now because I am directing, and I might be editing or whatever, but it is still where I want to be most.

I couldn’t have possibly imagined in a million years that this would happen. The fact that this quite personal thing has turned into a publicly consumed phenomenon is quite special. My sister was the very first person I hired. I really used the show as an excuse to get her to move to LA. We have been writing together since we were kids. She is my first writing partner.

When I first pitched the idea, Amazon Studios were the only ones who really wanted it and because they were just starting we didn’t even know if that was viable. Now it feels like a very safe place. HBO was interested, but they wanted us to do some developing and it maybe would have taken a few years. Amazon went after it really vigorously, and are involved, but with a very light touch. I think the fact that the audience can take it all in one go if they want to and really go into their own experience with it shapes what we do a little. It is a much more involved experience, when it comes to watching and bingeing. We try to think about when people might stop and when they might keep going, in a natural way.

In the writers’ room we plan, but it always changes. Things grow and change and take unexpected turns just like people do. We feel like the souls of the Pfefferman family are real – and they become more real to us with each series. They are really growing. When I see those early series I can’t believe how young Josh and Ali look, like babies.

Six Feet Under was a very similar vibe. I tried to learn from Alan Ball, who led that room. He used to tell us: ‘Just believe the family exists in the centre of the room, and then you all sit around and conjure them up.’ We are like that with the Pfeffermans. We want them to tell us what they want, we want that open feeling when the show starts to write itself, letting the characters come to us in dreams or while we are in the shower.

The writing itself can be tough. I never write when I am trying to write. I have to read the previous draft, take a walk, have a bath, live, think, dream, love, laugh and wait for the inspiration that says, ‘Here is the new scene!’ and only then do I sit down at a computer.

It is a different kind of all-consuming than it was at the beginning. It is a little less painful in a way. I think the show still has dark elements, but we are able to hold on to them a little bit more loosely and let things happen. I don’t feel quite as urgent about trying to collect the pain as I did at the beginning. I had wanted to have my own show for such a long time that in the first couple of years we almost felt like in a race against time. Now we can let the Pfeffermans do their thing and not feel we have to convey an agenda. I am hoping it can continue for many years.”

Alec Berg, Silicon Valley: ‘One thing we know is that failure is generally funnier than success’

Alec Berg is the showrunner and an executive producer and director on HBO comedy Silicon Valley, which follows five young techies trying to make their fortune in a startup called Pied Piper. Berg previously worked as a writer on Seinfeld and on Larry David’s Curb Your Enthusiasm and has four Emmy nominations for his writing. Silicon Valley is in its fourth season, and Berg is currently leading the team writing series five, which will air next year.

“Every year we start the writing process by saying: ‘What are the big-picture issues in the real Silicon Valley?’ And: ‘How do we get at them?’ We have dealt with gender issues recently. The big one now is privacy. On the one hand, it is easier to steal from reality than make things up. On the other we have to be very photo-real, which takes a lot of research.

Silicon Valley is a very different thing from Seinfeld or Curb Your Enthusiasm – and harder to write in that those shows were not serialised. It is pretty unique, I think, to try to create a narrative arc of this length in a comedy show. It is not just a day in the life. This is about people who are trying to accomplish something and the big question is, can they accomplish this thing without selling their soul? Every episode has to be a step along that journey.

On Seinfeld there was no writers’ room. Every writer would sit in their own office and work on their own episode. And then you would run it by Larry [David] and Jerry [Seinfeld] and they would say, ‘more of this’, or ‘steer clear of that, someone else is writing the same thing’. On Silicon Valley we have 10 or so writers in the room. We generally all outline together. Then one writer will pick an outline and write a draft. Then the rewriting of that draft is done in smaller groups. You can’t rewrite with 10 people. It’s usually me and the writer and one or two others.

It is a fact of life that whatever you are writing expands to fill the time you have. If we had six months to do one episode, it wouldn’t be enough time. It’s never enough time. The maddening thing is that until you have a deadline, psychologically, it is impossible to make good decisions. You’re never done, but it gets to the point where this is as good as we can make it in the time that we have.

In that sense with Silicon Valley, it is always: anything we have that works goes in. I have never heard anyone say, ‘That’s great! Let’s keep it on the shelf for next year.’ In season one there was that great thing where you could say, ‘Maybe this is the show, maybe that is the show.’ ‘Put this in, this can be the show!’ But the more you do it, the less freedom you have. It becomes more: ‘That’s not the show, that’s not how we do it.’

One thing we know is that failure is generally funnier than success. Every once in a while, we get to the point in the story where the guys in the show have a big win, and then we sit down and say: ‘Let’s write three episodes where things are going great for them.’ And we just can’t do it. It is too boring for the audience. The audience is invested in the characters and wants them to succeed, but if they do succeed, it is not interesting.

My own curse is I now have 25 years of ideas I can’t use. I don’t think I am any better at coming up with good ideas, but I am better at knowing what bad ideas are. I used to think a third of what I wrote was pretty good, now it is about a 10th. Quite often the only way we know something works is that we have written every other possible version of it and it works better than the other things. Even then you are not sure. We are writing things now that won’t air for nine months. Some things are funny now, but won’t be so funny in nine months. Just occasionally the exact right thing comes along at the right time.

One of the strange things about this format is writing without an ending. The first four seasons on Silicon Valley, we pointed the boat out into the middle of the ocean and set sail. We are now starting to have conversations about where we are headed. Season five doesn’t feel like the end, but season six or season seven might. Season five is about half done. We start shooting at the end of October. And then there is constant rewriting of the stuff we are shooting. We never have any idea of what the last two or three episodes will be. In that sense, you can never escape this thing. The shooting crew comes in for three months, and they are kind of nomads, going from one thing to the next. They will often ask me what I am working on next. I will say: ‘I’m working on this. Just on this. I do this all the time.’”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion