TV, mobile and the living room

"I also want to share some additional thoughts on Xbox and its importance to Microsoft. As a large company, I think it's critical to define the core, but it's important to make smart choices on other businesses in which we can have fundamental impact and success."

(Translation - Xbox is no longer core to Microsoft) - Satya Nadella

The tech industry has wanted to get to the TV for decades. For a long time it was widely assumed that PCs were only a transitional device and the normal consumer computing experience and ‘interactive media’ experience would happen on the TV, with a ‘ten foot’ user interface, powered by the ‘information superhighway’. TV would become ‘interactive TV, and that would be a big part of how ‘computing’ came to normal people.

Of course, the tech industry had made its way to the TV, in closed, single-purpose devices: games consoles on one hand and CATV set-top-boxes on the other. Tech tried to use these as bridgeheads: games consoles went online, partly because they should as games devices, but also as a step towards a larger vision, and Microsoft also tried the other route, buying WebTV.

But none of this worked. None of the attempts to prise set-top-boxes away from the cable companies or add any interactivity beyond a better EPG went anywhere much. Xbox and Playstation going online became important for games, but not much more. Attempts to move the actual PC into the living room (Windows Media Centre, Apple’s Front Row) are probably best forgotten. (I could also mention smart TVs, but really, why bother?) So you could argue about whether Microsoft or Sony did better in the console wars, but it doesn’t really matter for that broader vision (and of course more and more gaming will shift to mobile).

Today, we have another wave of products trying to get there - the Chromecast and the (new) Apple TV, which are really iterations of a previous wave of products (Vudu, Roku, Boxee) that never quite went mass-market either. (There's a complex discussion here about content availability, most of which is very specific to the USA.) But what interests me is that both of these are really about turning the TV into dumb glass - a peripheral for the smartphone. The Chromecast doesn’t even have an on-screen UI. They’re both about the smartphone market: they're about selling phones (they're too cheap and low-margin to make much money of themselves and most of the content money will go to the content industry), and they come from phones.

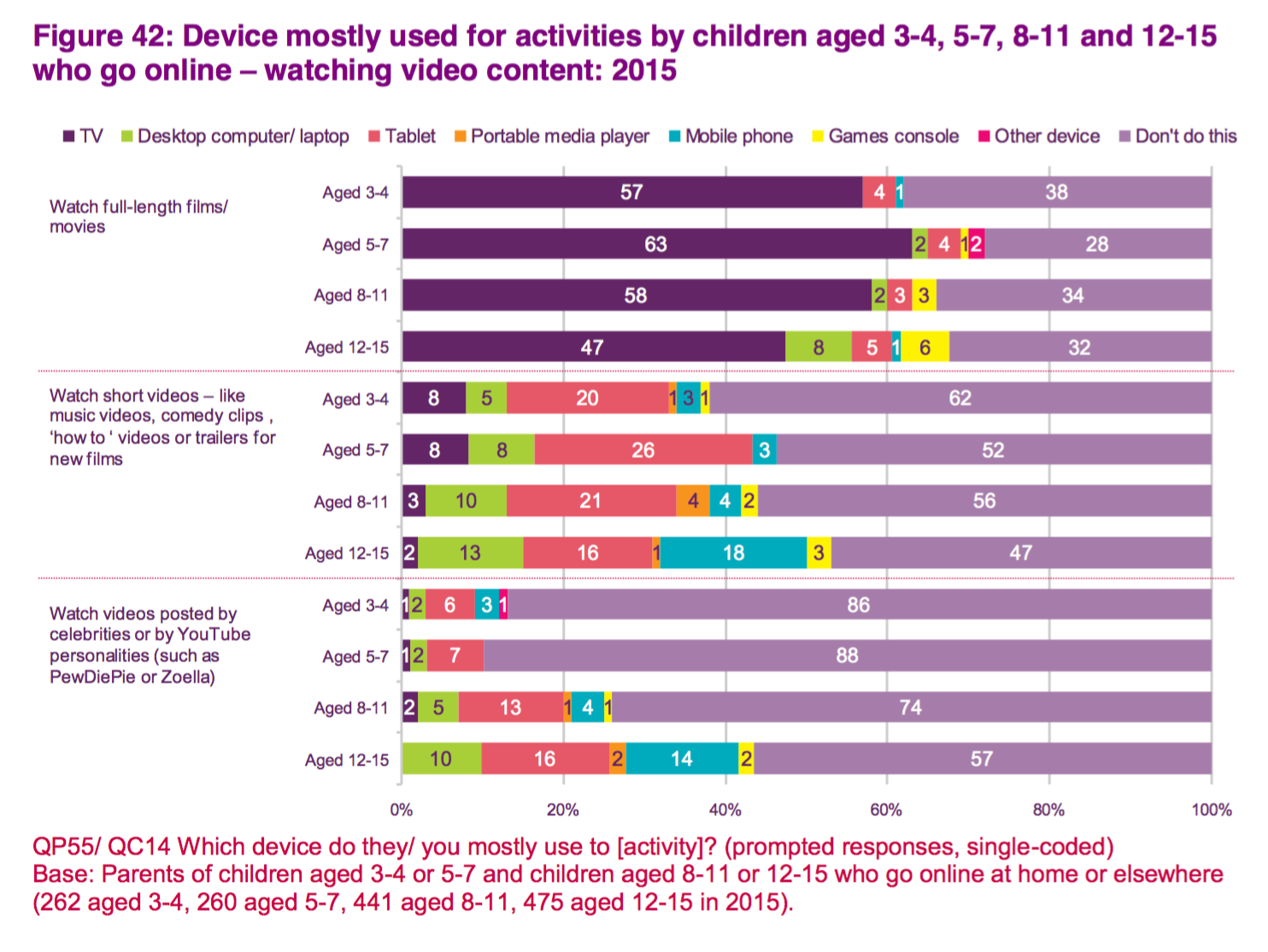

That is, even if Apple or Google finally 'win', and get their device connected to every TV in the developed world, it's something of a sideshow. The TV isn't the end point for consumer technology anymore, in either sense of the term. The consumer computing revolution went and happened anyway, without ever touching the TV. First the web, not ‘interactive media’ on the ‘information superhighway’, drove the PC into every home in the developed world, and now smartphones take a truly personal computer into every pocket on earth. And it turns out that smartphones and tablets are the way computing gets into the living room, and the way that the tech industry gets hold of video content, whatever that will mean. (This, in case it isn't clear, is why Satya Nadella said that the Xbox is no longer core to Microsoft's strategy.) There was a wonderful quote from CBS this autumn that they’re less worried about PVR ad-skipping ‘because people are too busy with their smartphones to bother skipping ads anymore’. You can see the shift pretty clearly in this chart from the UK: short form is all about smartphones and tablets, and so, increasingly, is long-form as well.

Why would you watch a film on a phone? This is why.

There are two things that I wonder in all of this.

First, how much of the linear schedule actually goes away, as content restrictions and UI friction finally falls away? Does everything except live events and especially sport fall off and everything else goes to on-demand, or does the passive, lean-back, ‘just show me something’ remain a large part of the large-screen experience? To the extent that viewing does move, this changes the distribution of watching across different types of content

Second, how much, really, do we need a large screen, and how much does it remain something that’s just there, and turning on sometimes, but used less and less, with the thing we hold in our hand actually a better watching experience? And for what kinds of content?

These are obviously linked - if we watch lots of big-budget event drama then we’ll use the big screen more and probably also use the linear schedule more. This is a little reminiscent of Hollywood’s embrace of spectacle in response to TV. So the stronger the linear schedule, the stronger live events, and the stronger big shows are, the more the big screen matters (even if just as dumb glass). The more TV changes, the more it moves device. And then, do you put that event drama you’re sort-of-watching onto the big screen so that you can do more important stuff on your phone, and look up the wikipedia page to tell you what happened when you weren’t paying attention? Maybe it's the small screen that really gets the attention either way.

Finally, this is a case study of open and closed approaches. Games consoles' closed ecosystem delivered huge innovation in games, but not in much else. The web's open, permissionless innovation beat the closed, top-down visions of interactive TV and the information superhighway. The more abstracted, simplified and closed UX model of smartphones and especially iOS helps to take them to a much broader audience than the PC could reach, and the relative safety of installing an app due to that 'closed' aspect enables billions of installs and a new route to market for video. It's not that open or closed win, but that you need the right kind of open in the right place.